Secrets & Urban Legends of UCSD

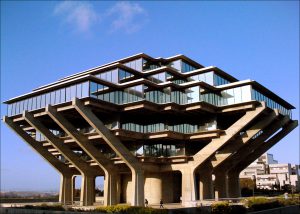

The University of California, San Diego (UCSD) has a reputation for being one of the best schools in the country. Its world-class facilities and proximity to the Pacific makes it the ideal place to study the sciences, especially marine biology. And being founded during the time of the Berkeley riots and considerable civil unrest nationwide due to the Vietnam War, the university is also steeped in war history and revolution. Some even used to claim that its campus layout was designed to ward off protesters and rioters; its long slit windows and jagged edges, they claimed, would make it difficult to move quickly (in reality, its design was fashioned so because Brutalist Architecture was in vogue).

In talking with UCSD alumni, discussion about the underground tunnels quickly came up — which is a common urban legend among many students. A lot of these theories have been debunked, but UCSD still remains one of the more mysterious campuses in California. Here are a few secrets we discovered in and around the university!

[image courtesy of San Diego Urban Exploring Meetup Group]

A Network of Underground Tunnels

Tales of secret underground tunnels have been circulating among the student body for years; according to urban legend, the school built them during the 1960s to provide accessible routes for the National Guard in case of rioting. This has proven to be more of a conspiracy theory than anything, however. Years before anti-war protests became common on campus (around the 1960s), engineers had built a network of underground tunnels designed to house utility pipes, electrical fixtures, and communication cables. The university placed all underground utilities here so that regardless of later construction, they would always be accessible.

The tunnels were also designed to help support the growing campus population and efficiently connect the new buildings stretched across campus. Then UCSD became a hotbed of protests against the Vietnam War, and the rumor mill began. Today, the tunnels are primarily used for their original purpose – channeling utilities and cabling below the bustling campus above. They’ve become a crucial part of the university’s nationally recognized power grid, which cuts down on energy costs by moving heated and cooled water between buildings for air conditioning.

The tunnel networks are rumored to be underneath Revelle (which provides steam and utilities to the science buildings and dorms) and Geisel Library. There is allegedly graffiti depicting Nixon and Vietnam, as well as magnetic tapes stored down there from when UCSD recorded satellites in orbit and old lab equipment. Unfortunately for all you adventure-seekers, they remain strictly off-limits to the public!

[image courtesy of UCSD]

Self-Immolation Memorial

George Winne, Jr. was a 23-year old American student who, in protest of the US involvement in the Vietnam War, set himself on fire in a deliberate act of self-immolation on May 10, 1970. He placed a sign next to himself saying “For God’s sake, stop the war.” SRS Police responded quickly, smothering his body to put out the flames. Winne was rushed to Scripps Hospital where he later died from 2nd and 3rd degree burns over 94% of his body. He remained fully conscious until his death, stating that his choice was “very personal and spiritual,” and instructed his mother to write a letter to Nixon demanding the cessation of the Vietnam War.

For years, the only tribute to his death was an unmarked memorial on the east side of Geisel, which was an artistic skeleton imprinted on charred bricks. Sadly, its location was nowhere near the actual place that Winne self-immolated; Revelle Fountain stands there today.

More recently, a Peace Memorial has been erected adjacent to the Revelle Plaza Fountain and features a marble plaque complete with a light installation. A bench was added to the space as well as a few trees to give students a place to remember and commemorate the campus’s protests for peace. An inscription on the memorial reads “For George Winne, Jr., the student activists of May 1970, and all those who continue the struggle for a peaceful world.”

Graffiti Stairwell/Art Park

Wall writing at UCSD dates back to 1971 or earlier, and quickly became systematic and enduring throughout campus until well into the 1990s. The art of free-for-all graffiti writing came to its final demise in 2013 with the painting of HSS East and Mandeville West along with radically increased rule enforcement – previously, Mandeville Building housed a colorful stairway completely covered in Graffiti, which was updated almost daily.

Now, there is an official Graffiti Art Park that has been sanctioned for just that; students are free to utilize eight double-sided, plywood billboards — 16 huge canvases — for any kind of art they please. It’s located near the Student Center, in the eucalyptus grove east of Porter’s Pub and south of the Mandeville coffee cart.

Secret Gardens

There is a plethora of hidden gardens on the UCSD campus. Behind the historic Che Cafe lies a mulched pathway leading to a quarter-acre garden, newly renamed Roger’s Community Garden in honor of Roger Revelle.

Similar gardens have popped up around campus, including Pepper Canyon Urban Farm at Sixth College, Ellie’s Garden at Eleanor Roosevelt College, and Earl’s Garden at Warren College. This on-campus farm-to-table approach has become so popular that the school is now offering more environmental science classes and student organizations are getting involved. They’ve also partnered with regional farms to help supply local, organic produce to meet the University of California requirement that 20% of food provided on campuses stem from sustainable sources by 2020.

[images courtesy of Wikimedia]

A Secret, Elite Postwar Science Team

Incredibly, there exists a tiny, independent, nationwide group of elite scientists who discuss and research cerebral scientific questions, mostly for the government and military. The group is simply called “the Jasons,” and they are indeed very secretive — much of their work is Classified. The group’s otherwise quiet existence rose to the surface recently when Jason Project co-founder Keith Brueckner passed away at the age of 90. Brueckner, a UC San Diego physicist, founded the Jasons in the late 1950s with the help of three other physicists.

According to sources, the Jasons carry out most of their deliberations in a building they lease at the north end of the General Atomics campus on the Torrey Pines Mesa, where they’ve met for years. The sessions mostly occur during a 6-8 week period during the summer. Their non-classified, less clandestine work includes such things as analyzing the likelihood of large-scale terrorist attacks and figuring out better ways to distribute people’s private health information. It’s a distinctively elect group; there are only about 50 members, each of whom is considered to be among the best in their field. The group operated in strict secrecy until 1971, when the New York Times published a classified history of the country’s political and military activity in Vietnam. The release of the papers occurred during the height of anti-war protests, and included tidbits of information about the Jason’s work as well as the name of some of its members.

[source: The Jasons: The Secret History of Science’s Postwar Elite by Ann Finkbeine and the UT]

A War-Focused La Jolla

Before UCSD existed in its current location in La Jolla, there was Camp Matthews, a United States Marine Corps military. The training base was in commission from 1917 until 1964, when it was decommissioned (a memorial plaque can be found on campus) and the land lease was transferred to the University of California to be part of the new UCSD campus. Over a million Marine recruits received their marksmanship training at Camp Matthews.

According to sources, many local citizens were preparing for a possible Japanese invasion while World War II was just beginning. Cement-encased bunkers were built all around Mount Soledad, though almost all of them, including some in the Muirlands, were all but destroyed in the last 40 years.

Other higher elevated grounds also had military uses. According to KPBS television, even the tower of the La Valencia Hotel once served as a lookout and observatory for military activity at sea. WWII fire-control stations were said to be located near Hermosa and to the west of La Jolla Country Club, as well as atop Mount Soledad; though again, much of these were destroyed in the 1970s.